I don’t often find myself writing about work. Partly, I suppose, because this blog is about things that inspire me, and just on its own terms, that’s a slightly different angle; partly, perhaps, because if you wanted to find out what we’re up to, I’ve always been of the view that it’s a few clicks over to the architecture pages where I am sure a few readers have had a browse from time to time.

But for a long while now, we’ve been working on a project in South Wales: a small group of houses, one of which we’re also decorating and furnishing. On Thursday and Friday, we moved in the furniture and the finish line is almost in sight. Ive got to admit: it’s one of the strangest projects I could possibly work on, and from time to time I need to pinch myself to make sure it’s real.

The site is on the edge of a vast decayed wasteland, near Port Talbot, called Llandarcy, and we’re embarked on a strange case of creating a new reality out of something that was once part of the industrial heartland of South Wales. For seventy years, between 1918 and 1998, here was a massive oil refinery, set up by Churchill shortly after the Great War. The land was chosen because of the proximity to Swansea Docks, where crude oil could be imported by sea from the Middle East and the refinery operated by the Anglo-Persian Oil Company – the forerunner of BP.

At its peak, in the 1970s, Llandarcy was one of the major employers in South Wales, with over 2600 workers on the site. This is what it looked like then. Majestic.

I couldn’t help but love these book illustrations from a 1953 guide celebrating the completion of the refinery (which I found and are written about on an interesting little blog that you can find here)

The optimism of the sparkling stainless steel piping is tangible. Something we could use a little more of these days?

By the mid 1990s, the refinery was redundant. And you can only imagine the pollution that had flowed from 80 years of heavy industrial use – most of it produced in an era where environmental standards were non-existent.

A bold scheme was slowly put into place to reconstruct Llandarcy: to clean the toxic soil, and create a new brownfield development of mixed-use, houses, shops, offices and small-scale, clean factories, based in part upon the principles set out at the Prince of Wales’s new town of Poundbury, on the edge of Dorchester.

We’ve been involved on and off for about 5 years now, since 2008, when I first was asked, with my great friend Ben Bolgar from the Prince’s Foundation, to plan this small group of houses. They were commissioned by BP to act as a demonstration of the sort of quality they wanted to achieve on the site. Together, we selected one of the most special parts of the site – simultaneously one of the most beautiful, but equally, the most polluted parts of Llandarcy. It took a long while to get the project off the ground, in those difficult days when the banks were collapsing and development juddered to a halt. But they slowly got underway. Our client then commissioned me to work on the interiors and furnish one of the houses – again, to place a marker in the sand of what it means to create a house that, just, feels… right. “I don’t know a thing” said David. “Do whatever you think best. I know I’ll love it”.

So we set out and started slowly buying bits of antiques here and there as the houses slowly started construction. The budget was sensible but not crazy… A question of spending wisely (by and large) rather than going mad. As we all know, old and unloved bits of furniture in regional auctions sell for a song. And with limited resource we put everything together over a long period of time. I’ve got to admit – having plenty of time is the biggest single thing you can ask for in making a house.

On Friday we moved everything in. So here’s a few photographs. I’d be fascinated to know what you think.

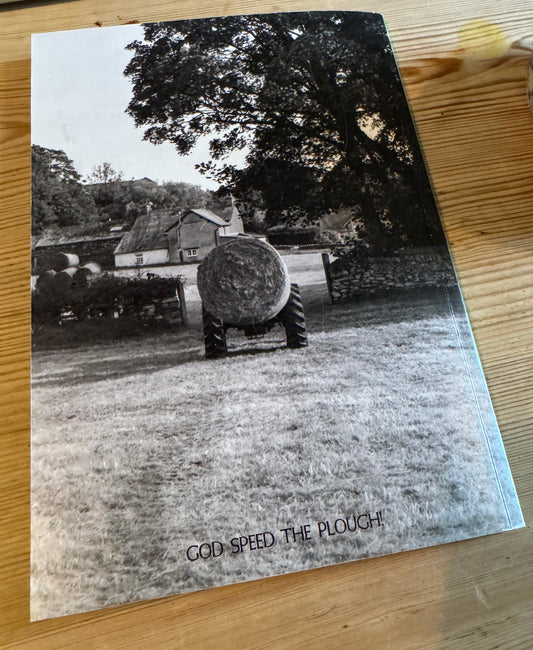

The site sits in the middle of a vast industrial wasteland.

You see what I mean about weird.

The eight houses are built on the edge of a Site of Special Scientific Interest that, when I first saw it, was drenched in heavy crude oil. Today, that land is cleaned, the wetlands are restored and humming with wildlife, and I couldn’t really imagine a more beautiful setting to be building new homes.

The houses are approached from the south and you first see a stone-built visitor centre that has the red corrugated iron roof. I love corrugated buildings. I think this material should be used a lot more. It’s plain, honest, cheap, highly effective, and looks fantastic.

There’s something strange about these houses. In the middle of all this chaos, the strangest lunar-scape I’ve ever seen, they already seem settled. Although they were finished just a few weeks ago.

A terrace of small houses are incredibly simply constructed. Tiny touches, like knocking off the corner of the blocks to form curved reveals, can make all the difference. The entire site is built of solid terracotta block walls – a very sustainable material; the houses feel solid and quite special within and without.

The little terrace is the counterpart to the three larger houses that you’ve already seen in the photographs above. Planting beds are planned in front of these houses (I promise). One of the things that I like most of all: the windows between ground and first floor were all drawn lining up. No offence to Welsh builders… but… this is not what we got! Thank goodness. The houses have a freshness, a reality, by being just that little bit wrong. You can’t plan this sort of thing, and you can only be grateful when it happens.

Here are a few photographs inside.

Local Blue Pennant stone flags on the floor. From about 13 miles up the road, and a very beautiful stone indeed. We used it to make a fireplace as well, and it is the stone that forms the bastion wall outside, as well as the stone window surrounds.

Welsh slate in the kitchen.

Slightly surreal. 10 chairs wait silently for the refectory table, that is being made in new oak by my friend Greg Hewett. The Arts and Crafts chairs are beautifully handmade by Lawrence Neal, who should be a subject for this blog alone. They are completely and perfectly satisfying.

Prince of Wales investiture chairs flank a handsome old dresser. Chandelier by The English House; rug by Roger Oates; curtain fabric by Robert Kime (all curtains beautifully made by Tinsmiths). More mochaware on its way…

The oriel room.

The sitting room

A glimpse into the study which, I decided, needs (like my kitchen in Dorset) a wishbone chair to pep up the volume a bit. Sharp eyed readers will recognise the geological map, now on loan from the Old Parsonage. It fits rather beautifully here!

The main bedroom

And guest bedroom (pictures still to be hung). Block printed curtains by Soane Britain (one of the mad but worth it moments).

In the attic

landings and stairs.

It’s a curious thing. Four days ago, this house was completely empty. Within 24 hours, all the furniture was brought in and set. Now, I’ve got to say, with a little bit of imagination (and one or two lamps, and a few more bits and pieces) it really does feel lived in. Perhaps, it has to me admitted, some of my prejudices are not far under the surface. You won’t find a TV but you will find a lot of old books, and plenty of hunsletware.

But what I find strange is this. Five years ago, this site was heavily polluted industrial wasteland. Twenty years ago, it looked like this – a conglomeration of massive gas storage tanks:

It feels quite odd to be creating such an alternative universe. I can’t say our houses feel like the last answer to the question, ‘what is it to build new houses today?’. Maybe they are one answer. Well, perhaps the architects amongst the readers will be grinding their teeth at that suggestion… and so I’m not even quite sure of that.

Twenty years from now, the rest of Coed Darcy will be constructed and these houses will be completed joined to the first phases now being constructed. Streets will lead down to them where currently giant tracks cut through the landscape. Shops and cafes will be a short walk up the road. The neighbours will be coming over for a cup of tea. Now – they sit completely alone and isolated, in the middle, literally, of nowhere. Yet they have a sense of place, of inevitability, and of timelessness, that I must say surprised me.

I’d be very interested to know your views. Positive or negative, or somewhere in between.

And if you’re an artist or poet or writer, fascinated in the post-oil, post-industrial age, and think you could enjoy living (for free) in the middle of nowhere in South Wales for a few years, please get in touch. I’m not sure, but it just might be that something could happen.